At the Augmented & Virtual Reality roundtables at GDC 2015, there was consensus that moving a player through space made them uneasy. While in the future, I’m sure we’ll discover interesting tricks to ease the transition, what if we aren’t worried about that, and instead an entire interactive narrative experience happens in a single space?

This multi-part series examines inspirations for interactive narrative design in small spaces. These reviews are going to at times sound oddly mechanistic, as the goal is to focus on moments of potential narrative agency and player interaction. There is a separate movement towards Virtual Reality film, where one would semi-passively take in narrative in a virtual environment, but, as usual, I’m more interested in the interactive stuff.

In the first part of this series, we’ll look at two mysteries: Rear Window and The Lady Vanishes, both by Alfred Hitchcock, and one movie that is an action-mystery (?), Snowpiercer.

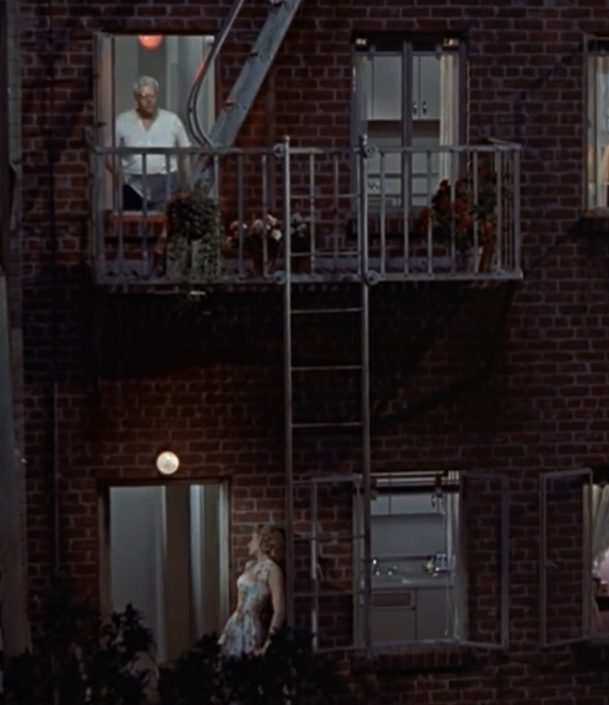

A photojournalist is confined to his apartment after breaking his legs. Bored, and becoming stir-crazy, he uncharacteristically fills his time by watching his neighbours out his rear window. Based on subtly suspicious behaviour, he suspects one of his neighbours of murder, and has to convince his able-bodied social connections to investigate for him. The entirety of the viewpoint of the story takes places in the protagonist’s apartment.

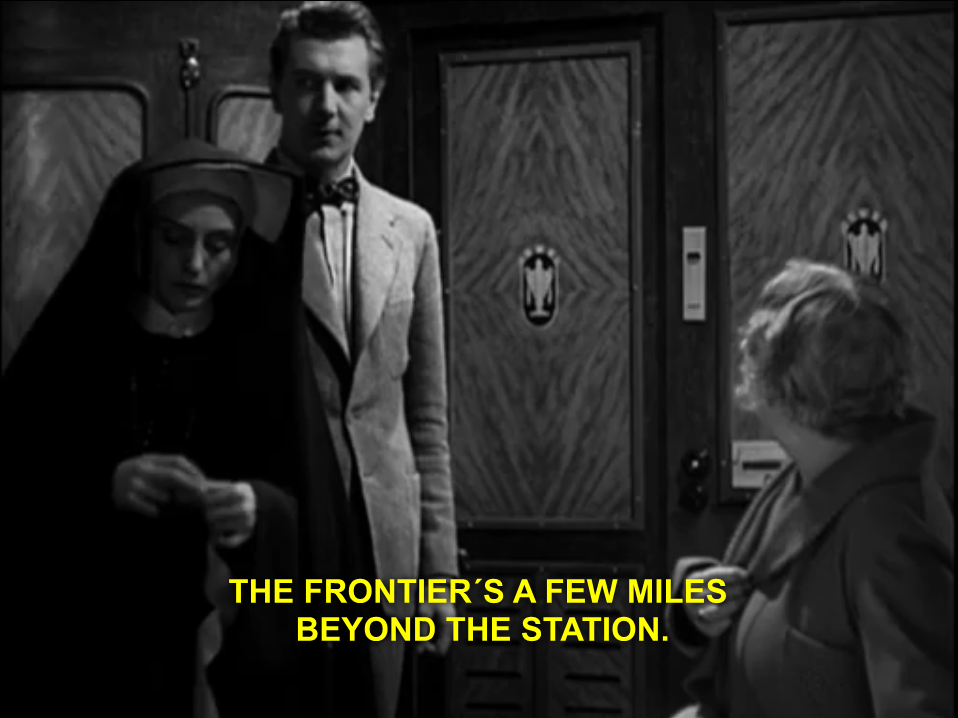

A tourist is returning from a vacation to her native England. After she bumps her head while boarding a train, she is aided by a plain older woman. When the tourist awakes from a nap, the old woman is gone, and no one on the train remembers seeing her. The tourist begins to doubt her memory while scouring the train and its occupants for any evidence of the old woman, all while accused of being delusional. The film begins with a little under half an hour of character exposition with an ensemble cast in a hotel before we board the train, and spend most of the time going back and forth between three cars (dining, cabin, cargo).

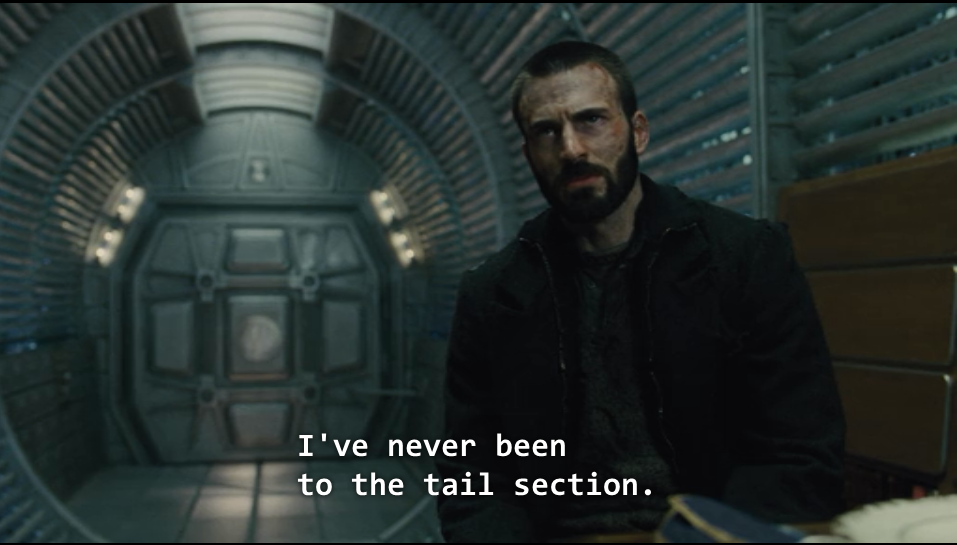

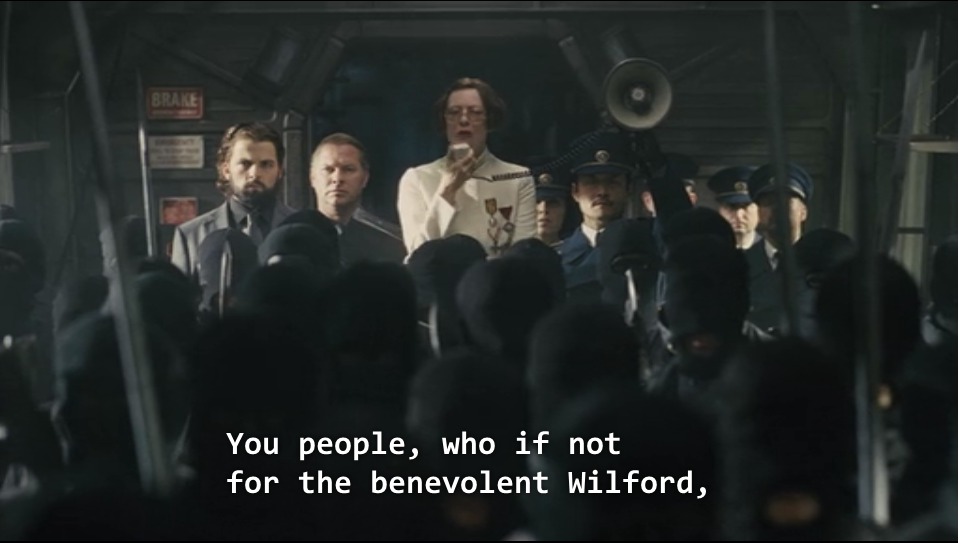

A fully self-contained train is in constant motion on a track around an Earth plunged into freezing by an apocalypse 17 years previously. The train is about 1000 cars long, and arranged in social hierarchy from the poor people in the tail section, to the rich at the front. The story follows the leader of a revolt starting in the tail section, trying to gain access to the less-crowded front sections. We follow the protagonist from the rear of the train all the way to its front.

TALKING POINTS:

In all cases, there is a sense that the confinement in the environment is unnatural and unsettling, and that what the protagonist witnesses or believes may not be the truth. This is made worse by their confinement; they are restricted from verifying facts for themselves by the environment; in this way, the environment is self is a secondary antagonist.

Both The Lady Vanishes and Snowpiercer take place on trains, however individual scenes, whether action-oriented or not, all take place in single cars. To be practical, you could start each positionally-tracked VR scene in a new car, and then have whatever transition you’d like between them, as they are relatively rare. The individual train cars in both movies have a drastically different feel to them, especially Snowpiercer, whose train cars sport a high variety of style.

In The Rear Window, the protagonist is trapped in his space, most of the time in his wheelchair, and all the action happens outside, him being the primary witness and powerlessly and tenuously interacting with the outside.

Both Rear Window and Snowpiercer take place over an extended period of time, while The Lady Vanishes only skips time when the protagonist dozes off. The initial tension of the first two comes from being stuck, but in The Lady Vanishes, it comes from a disappearance and that everyone else on the train believes the protagonist is mentally ill. Because the space is confined and very finite, the protagonist asserts that the missing person must be on the train, as it hasn’t stopped, and begins an exhaustive search for clues.

In our regular non-dramatic lives, the average human being spends much of their time in confined spaces, whether at home or at work. To contrast, the primary action in most interactive narratives is to move through space; in interactive narrative where you’re a silent protagonist, moving your body may be one of the only ways you can express yourself and advance the plot. I couldn’t find the reference, but Ben “Yahtzee” Croshaw has previously expressed the work of video game players as moving characters around on dolly carts, shoving them together in the right combinations to induce conversations that further the plot (in his video game analysis show Zero Punctuation).

In both The Lady Vanishes and Rear Window, the protagonists have a strong conviction which everyone else doubts, and they at times themselves doubt, but they slowly bring people over to their side. I’m not well-versed enough in Hitchcock to know if this is common in his works. I wonder how it would be possible to have self-doubt of a conviction in an interactive mystery narrative. Usually, the way it goes is “The thing that happened is X, collect the evidence and (if it’s undetermined) figure out who did it”. The narrative push of the game would cease to exist if the player/protagonist determined that the result is “everything is fine, nothing to worry about”, as all the other characters in the Hitchcock mysteries insist. Curiously, in both cases, if the characters gave up their convictions, no harm would come to them, as the problem they’re trying to solve in no way directly affects them, and they only come in harm’s way through their insistence. I like the agenda Hitchcock is peddling, though it could be construed as “your hunch convictions are always correct no matter how much evidence you get against them, initially”.

The interactions between the protagonist and their environments vary significantly. In The Lady Vanishes, most of the interaction is social, though one clue-hunting sequence suddenly turns, surprisingly, into a combat sequence. Snowpiercer, after exposition, is mostly combat, with breaks where a series of increasingly important secondary protagonists will pontificate, then be disposed of, oddly reminiscent to the progress of any *-Shock game. In Rear Window, the apartment is static and safe, while dynamic and dangerous events happen outside it, until a break of this established pattern in the finale. The protagonist has social interactions inside the apartment (convincing visitors of his convictions, other storyline interactions) and has to observe the outside very carefully for clues, using both his binoculars and telephoto lens. At one point, the protagonist has to direct the movements of another character trying to escape the antagonist in a Scooby-Doo like sequence across several stories.

In the modern day, texting would be used for coordination, but here it is through aggressive gesturing. Curiously, the characters that the protagonist is directing across the way don’t always listen to him, and take risks even when he explicitly instructs them not to. This loose control of another character, with their own impulses, would be cool to explore in an interactive medium, and it supplements the loss of control that the main character already feels. The final interaction available to the protagonist is no doubt designed to comically highlight their helplessness yet again: a long wooden scratch stick to get underneath his cast. The act of scratching is shown to be the most physically strenuous task of his day. Designing this with a quicktime event would no doubt excite David Cage.

Stray Notes:

Rear Window

– A series of observed events occur, without any verbalization, where the main character dozes off and wakes up during a single night, and sees the comings and goings of people. It is uncertain how much time passes between these dozings. In one case, we’re shown a brief scene while the protagonist is shown to be asleep, an unsettling break in the consistent first-person viewpoint for the first time in the movie (around the 36 minute mark). This is the only moment in the film where the viewers see something that the protagonist doesn’t.

– The line “why don’t I slip into something more comfortable” appears. It’s too early in the history of film, so this comes off as completely innocent to the trope. Also, “please make me a sandwich”.

– The movie starts with him watching a lady across the way dancing to herself in pink lingerie.

– The protagonist is afraid of marriage, which is metaphorically treated as imprisonment, like being stuck in this apartment.

– The theme of captivity comes back again, where the protagonist and his fiancee are in love, but captive in their own worlds. His in always wanting to travel, her in her high-end New York lifestyle.

– People are able to enter the protagonist’s space without his warning or consent (other people seem to have keys, or the door is unlocked). This is pretty unnerving.

– Later, the protagonist convinces someone, who is able to actually walk around in the world, that something is up that needs general investigating. Since this is the 50s, they communicate by landline. Interestingly, were this a video game, the player would take the role of the person moving around in the world accomplishing errands, while a disembodied voice gave them assignments. In fact, the character on the phone who is out doing stuff in this movie refers to their tasks as “assignments”.

– The protagonists’ camera flash is used as a weapon (Hey there Beyond Good & Evil).

– The protagonist looking into other people’s windows, through frames into private lives, feels very much like the gaze through the frame of a film into the character’s lives themselves. The Rear Window is about film, duuuuuuude.

The Lady Vanishes

– This is the first appearance of Charters and Caldicott, two British characters obsessed with cricket, regardless of the gravity of their current situation. They went on to appear in several films and their own TV series.

– Nice clue mechanic: the protagonist recalls that the missing (and possibly non-existent) old woman wrote her name on a window in the dining car. She tries to find this again, but writing on a window turns out to be a short-lived form of proof. This is a nice moment for the protagonist to convince herself that she is not insane (maybe), but still insufficient to convince anyone else.

– The poor people (in the back of the train) have no idea what goes on in the forward cars, or even what they look like. There’s one clever bit when the train turns around a tight corner, and people can see each other (and shoot at each other) from several cars apart.

– More so than The Lady Vanishes, the cars’ dimensions are all identical, but the difference of their interiors highlights the massive social differences in the train society.

One response to “Studying Narratives in Small Spaces, Part 1: Mysteries”

[…] socializing, I spent a long time staring out the window at passers-by from several stories up. Like the protagonist in Rear Window, I invented personas and relationships based on how and where people moved through space, alone and […]