This past year at Escape Character has been quiet, but very busy. Me + several collaborators have been iterating on telepresence interactive theatre. We have written and debuted three scenarios and are in the middle of writing our fourth. We’ve put on in-person shows in San Francisco, Toronto and London. We just started remote invite-only shows in December 2018, and will be publicly releasing our first show in February 2019 (announcement to come)!

What we’re making is pretty new, but you can think of it as:

* A premium role-playing video game, where you play as a party and every NPC is played by a real actor.

* A Narrative Escape Room

* A Choose Your Own Adventure, with a live actor and extremely open-ended choices

* Immersive Theatre you can access from anywhere.

* Dungeons and Dragons lite, with less prep required for audience members

* Training Wheels for LARP

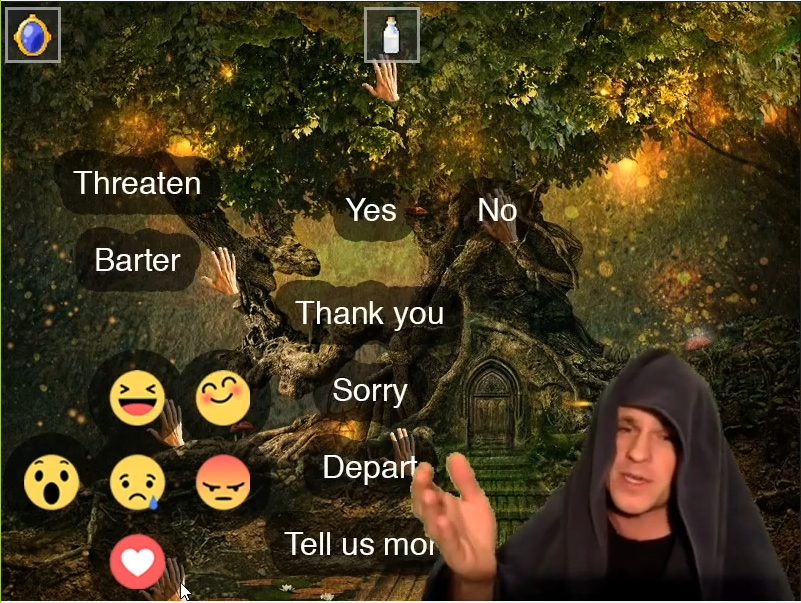

The biggest leap this past year is moving audience remote interaction from from voice to mouse. I’ll explain why, but first watch this excerpt from a recent playtest. In this video, I play two different NPCs. Every player can see each other’s mouse position, and hover over conversation options, or click to move the group around on the world map.

From the very beginning of Escape Character, the goal has always been to use streaming and other telepresence technology to enable performers to put on interactive narrative shows for intimate-size audiences. Immersive Theatre is a great medium which will define much of the next stage of entertainment, but currently it is difficult to access. It’s expensive because it requires custom physical venues, or because the audience for it tends to only exist in big entertainment cities (e.g. London, LA, NY, SF, Toronto).

For most of 2018, our setup was to have one performer play all the characters in a scenario, while 3-6 audience members were in the digital space as players. The players communicated with the performer by voice. Check the following video for excerpts from our scenario The Sea Shanty, by Tom McGee. The performer used VR equipment to play all the non-player characters, and all players used video game controllers. We did this in closed rooms with only the players, and at events where 40+ audience members were watching the players.

Why does voice not work?

- The Pressure of Acting. Many regular people are uncomfortable having to “act”. If you have a background in improv, or playing Dungeons & Dragons, it’s easy to forget how common this is. These people are still quite eager to participate, but often terrified of the (perceived) pressure of performing.

- Internet Lag. Think of any video call you’ve done. If you increase the number of people in the call to 4-8, the peer-to-peer lag, even if it’s a relatively low ping like 50 ms, gets so high as people negotiate trying to speak without interrupting each other.

- Moderation. You’ll always have people who are trolls, hecklers, or simply ignorantly impolite who don’t know how to share the space with others. Audio as a medium is single-channel; you can’t really have more than one person talking at once. We could build a muting system, but it’s way easier for the moment to avoid audio altogether.

- Environment. If the show requires you to speak, you can’t participate somewhere where it isn’t appropriate to, like an airport lounge.

- Anonymity. Part of the joy of engaging in immersive entertainment is the option to present as someone else. Theatre has for a long time known of the transformative power of mask, and having to use your real voice omits that option.

How audience use mice to communicate

Systems using live actors should take advantage of live actor’s ability to respond improvisationally to novel audience behaviour. If any audience communication system involved a poll, yes/no, or multiple choice, that’s an impoverishedly simplified form of live expression. One of the curious things about the depiction of ractors in Neal Stephenson’s Diamond Age is that actors were mostly used as mere voice actors, and it was AI systems that actually wrote and managed the interactive narratives in the Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. This doesn’t take advantage of the skills that improvisors have a-plenty! There’s a massively underutilized skill set of performers able to manage live storytelling and Escape Character exists to give these people a performance platform, and give audience access to immersive theatre remotely.

Our current conversational UI design is just a static image, almost like a Ouija board. The actor responds to where and how the audience positions their mice, as a whole but also as individuals. If you’ve been a live performer, you know this is like reading the room – something you say may elicit a whole-audience guffaw, or a chuckle from just one person, or made the front row gasp. This subtle input is currently missing from remote audience engagement systems. We’ve seen really clever behaviour audiences figures out on their own, like gesturing between two different options to indicate they want to combine them.

From one of our audience members:

I always knew where my colleagues were positioned in the decision space, and I could easily express my own positioning by moving my cursor or placing it in a default position (e.g., over on the right). The movement between options and movement on the map was parsable to me as a kind of continuous decision making, and the fluidity really underpinned the aesthetics of the team experience for me.

Get notified about when Escape Character opens up public tickets! Email us at contact@escape-character.com.

If you want to read more about our prototyping process, check out the article after a grant to work with UK-based artists GibsonMartelli: RealityRemix – Prototyping VR Larping

One response to “Telepresence Immersive Theatre with Mice instead of Voice”

[…] input to turn declarative sentences into AI behaviour, i.e. “bears chase sheep” * The ouija-board like interface in The Aluminum Cat, where remote audience interacted with a live performer using only their […]